not just a foreign-language elective, but the study of how languages are structured, including dialectology (Latin helps one decipher Romance languages, but linguistics helps one decipher all the others)

–

Table of Contents:

- Introduction

- Basics

- Vocabulary

- Progression

- Additional Notes

- Final Notes

- Overall (Images Begin)

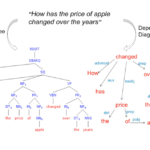

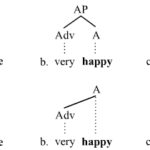

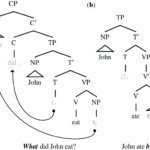

- Sentence-component Trees

- Language-family Trees

- Videos

–

Introduction:

There were so many problems with the mix-and-match English language (such as how people were formally taught to write it; quotation marks after punctuation intended not for the quotations, etc.), that the language as a whole, not just the roots of its words, had to be examined and called into question. Since then, Inisfreeans have also reviewed other languages, determining whether they exist as originally intended, where they can be improved, and so on. The results have contributed to keeping the languages exclusively used by the Inisfreeans incredibly precise, consistent, and easy to understand (not just easy to convey ideas/commands in/through).

-

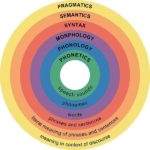

the scientific study of language and its structure, including the study of morphology, syntax, phonetics, and semantics. Specific branches of linguistics include sociolinguistics, dialectology, psycholinguistics, computational linguistics, historical-comparative linguistics, and applied linguistics.

–

Basics:

- systematic: characterized by order and planning

- phonetics: the branch of acoustics concerned with speech processes

- phonology: the study of the sound system of a given language

- morphology: the study of the structure of animals and plants –the branch of linguistics that studies the structure of words

–

Vocabulary:

- acronym: a word formed from the initial letters of several words

- affix: attach to –a bound morpheme that attaches to roots and stems

- allomorph: any of several different crystalline forms of the same chemical compound –a variant phonological representation of a morpheme

- allophone: (linguistics) any of various acoustically different forms of the same phoneme

- ambiguity: unclearness by virtue of having more than one meaning

- antonym: a word that expresses an opposite meaning

- blend: mix together different elements –a new word formed by joining two others and combining their meanings

- coda: the closing section of a musical composition

an optional element of a syllable, consisting of one or more consonants following the nucleus - compound: a whole formed by a union of two or more elements or parts –a word formed by combining two free morphemes in their entirety

- conjunction: the state of being joined together

- consonant: a speech sound that is not a vowel –formed by obstructing the flow of air as it is passed from the lungs through the vocal tract

- descriptive linguistics: a description (at a given point in time) of a language with respect to its phonology and morphology and syntax and semantics without value judgments

- prescriptive linguistics: an account of how a language should be used instead of how it is actually used; a prescription for the `correct’ phonology and morphology and syntax and semantics

- linguistics: the scientific study of language

- etymology: a history of a word

- semantics: the study of language meaning

- determiner: a determining or causal element or factor –a lexical category that co-occurs with nouns

- digraph: two successive letters –a spelling in which two letters are used to represent one sound

- diphthong: a sound that glides between two vowels in a single syllable

- homonym: a word pronounced or spelled the same with another meaning

- homophone: a word pronounced the same with another meaning or spelling

- inflect: vary the pitch of one’s speech –change the form of a word in accordance as required by the grammatical rules of the language

- morpheme: the smallest meaningful language unit

- orthography: representing the sounds of a language by written symbols

- phoneme: a distinct speech sound in a particular language

- phrase: an expression consisting of one or more words

- clause: a separate section of a legal document –an expression including a subject and predicate

- constituent: one of the individual parts making up a composite entity –a word or phrase or clause forming part of a larger grammatical construction

- rhyme: correspondence in the final sounds of two or more lines –a word or phrase or clause forming part of a larger grammatical construction

- schwa: a neutral middle vowel that occurs in unstressed syllables

- syllable: a unit of spoken language larger than a phoneme

- syntax: the study of the rules for forming admissible sentences

- synonym: a word that expresses the same or similar meaning

TBA: copy relevant parts from wiki

–

Progression:

- understanding how one’s own language formed

- understanding how similar/related languages formed

- understanding how differently-structured language formed

- understanding how a completely differently-structured language is likely to form

- practicing forming languages with different rules/branches that all those one is accustomed to using

- more TBA…

–

Additional Notes:

Almost every language on Earth is structured similarly, if not identically; they have declaratives, imperatives, interrogatives, greetings, and just a few syllables/sounds to describe almost everything their people will ever encounter (or can think of). While different alphabets may make some more difficult to learn than others, they are all based on sounds, writing, and simple concepts. Therefore it is relatively easier to learn a foreign language, even if it uses a foreign alphabet and/or syntax, than it is to learn a language that, for example, might not use an alphabet at all; perhaps it is just sounds without a written form, or just geoglyphs never intended to be conveyed orally/verbally. That is where linguistics comes in; linguistics allows us to determine if we are even looking at a language in the first place, then how best to make sense of it.

…

2024 January: Regarding “Heir” and “Heiress”: It is not necessarily that a suffix was added to a male word to make it apply to females; it could just as easily be that the original word was for females, and got shortened to apply for males (a truncation). It would be interesting to examine languages, including no-longer-spoken (“dead”) languages, to see if any languages worked the other way around; if some languages actually had longer words to indicate application to males, adding suffixes to female words to make them male-applicable word-versions.

–

Final Notes:

By understanding linguistics, not just languages, we can better decipher languages that are new to us. This goes beyond recognizing similar syntax; alien languages may not have any of the syntax we are familiar with at all (and some might not even have/need any (syntax) in the first place). To help us grasp what is being expressed to us in all languages, familiar/old and alien/new, we need to understand how and why all our known languages formed; it is in that… that we have our best chance of estimating which syntax/es are being used in any given language we have just encountered, as well as of estimating what sort of vocabulary/associations we are about to decipher/encounter (because some languages have no reason to describe plants, for example, if the language in question was developed to help machines on a world without any plants communicate with one another).

Furthermore, –and this is where it gets really interesting– understanding the principles of linguistics allows us to notice languages we might otherwise overlook, such as the one being used by the stars themselves to communicate with one another… and with the planets that orbit them… and with the stars their secretly-hollow cores contain. Languages often look/sound complex; they have many characters/letters/symbols (just count all the letters, numbers, punctuation marks, emojis, etc., in yours), such as Chinese (which has tens of thousands, a far cry from the few dozen English and most other languages use). To the untrained eye (or ear), our languages may seem like gibberish, …yet they have patterns, they develop in certain ways, and they have shown us that even a seemingly-random sequence of radio-bursts or other Morse-like emissions/transmissions… can be more than “background noise/static”; it can be the reading of a speech or full novel.

–

Overall:

–

Sentence-component Trees:

–

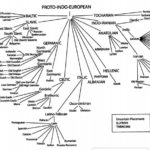

Language-family Trees:

–

–

Also see:

- This Culture That Came BEFORE the Native Americans

(minus the evil-tarded xian comment at end) - Michael Armstrong – “Night Linguistic = No + Eight” – Thunderbolts

Night = no+8

..

Noel = No El; absence of Elohim/God/s when Saturn and Venus no longer lighting Earth, causing a lasting darkness

–